The Summer I Worked in a Viking-themed Amusement Park

I was seventeen when my mom decided I needed a summer job. That wasn’t an altogether unreasonable expectation. Masterfully as I had skirted similar demands in the past, I found no valid arguments against attending a hiring fair for the soon to open Vikinglandet—The Viking Land.

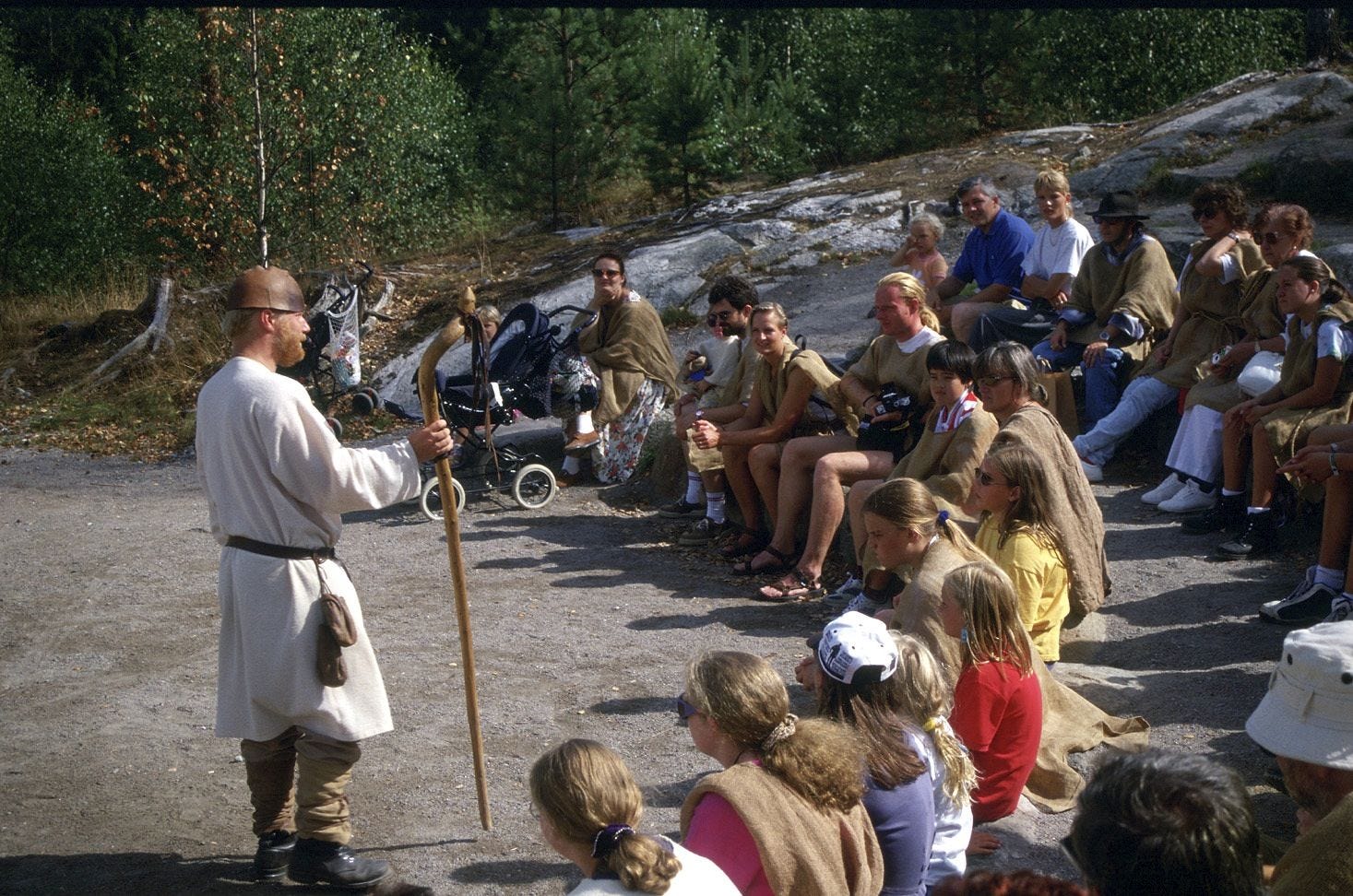

Vikinglandet was a new theme park from the proprietors of the Six Flags-style Tusenfryd. “Step into the land of the Vikings,” it boasted, “and be fully immersed in a historically accurate world.” Education and entertainment: Edutainment.

I went to the fair with three friends who possessed both service-industry experience and can-do attitudes, neither of which I was particularly well-known for. What I did have was shoulder-length hair that a hiring manager told me was very Viking-like. It was likely also why I was the only one in my cohort to walk away with a job.

“You spoke up three times during the group interview,” one of my friends noted, “timed perfectly to when the manager walked by.”

It was a fair point. Looking back, my competitive instincts might have gotten the better of me, seeing I didn’t particularly want the job.

Vikinglandet would turn out to be a disaster, business-wise, so my hiring was prophetic. The park closed after one season, during which I only worked four shifts.

Of the many rules we learned as part of indoctrination, the major one was that we had to wear our designated Viking costumes at all times. (Made of cheap polyester, just like Leif Erikson liked it.) To my infinite chagrin, I did not get any sort of dispensation from the rule, despite having to walk only thirty feet from the dressing room to a kitchen where I inexplicably had become the sole cook.

The second tentpole of Vikinglandet employment was the safety instructions. During my third shift, one of the more ornery managers started shouting questions at me about them. As I hadn’t read the fifteen-page manual, my answers were not good. (I also had a hard time taking a grown man in a Wal-Mart-grade Viking costume seriously, no matter how close he was to explode.)

Still, it was not enough to get me fired.

I suspect I got the cook position because H.R. had forgotten to assign me a more fitting job. Prior to hire, my kitchen experience centered mainly around the microwave, and good as I was at getting the popcorn just so, Vikinglandet had set the bar quite a bit higher. Helpfully, none of the training I received was in the kitchen.

On the menu were grilled lamb-chops, salmon, and an apple-and-honey dessert I never quite could figure out. I re-interpreted the dish the dozen times or so I prepared it, and I’m reasonably sure it never landed where Vikinglandet had envisioned. It’s hard to say, though, as, with all the dishes, I only had the ingredients to guide me. Authentic Vikings didn’t need recipes.

I never heard of any E. coli outbreaks that summer, so I assume my cooking wasn’t hazardous. An elderly lady even left a comment saying she enjoyed her meal, but I suspect that was out of well-meaning pity. Still: No illnesses that I was aware of, and one thumbs-up? I was defying my own expectations.

Twenty-six years later, and I look back at my culinary audacities with dread. Preparing lamb-chops can be a challenge, and I can’t help but wonder how many I served either raw or burnt. None of the eight I prepared were returned, so either they were edible, or Vikinglandet’s guests had resigned to mediocrity.

My co-workers, managers aside, were friendly yet demoralized. Some had counted on decent paychecks, and the lack of shifts was dour.

For the most part, the park was empty, and those who did visit looked longingly over at the neighboring Tusenfryd. In the dressing room, some of the professional actors—the Viking equivalents of Disney World’s Mickey Mouse—were justifiably starting to fear for the renewal of their contracts.

“Why don’t you step out of the kitchen when it’s slow,” one of the actors asked. “You can be a real Viking—the kids will love it, want to stay longer, and dad will order another beer.”

Even if that was the case, there was no way my seventeen-year-old self would want to attract more attention to myself than the costume already did.

The only interaction I had with visitors that summer was a kid yelling about how I didn’t look period-appropriate when carrying my backpack to the kitchen. In retrospect, I will concede he had a point.

As my probationary period came to a close, I got no signals if I was to be kept on or not, and with odds overwhelmingly favoring the latter, I decided to call it quits. I dropped my costume off with the managers, with a quasi-snarky, “I assume you’re not keeping me on.” They looked less than pleased.

In retrospect, I assume the park must have gone from being over-staffed to having a shortage of employees. No way was I the only person to leave, and me walking out meant losing the bottom of the barrel.

A few months later, the season was done, and the park closed. The following year, it was incorporated into Tusenfryd, which converted most of the land to new, traditional rides. Vikinglandet was relegated to a sub-section of the park and was completely shut down shortly after.

As for my friend who pointed out my lack of enthusiasm? He did end up getting a job as a Viking, after all. At Epcot Center in Florida. I guess he ultimately did win.